Welcome to our online suggested practise for the week number 71. We are now broadcasting a live teaching each Monday evening. If you would like to participate please contact us using the contact form on the homepage.

1.0) If you feel so inclined, begin by reciting the usual prayers (please follow below links for text). Alternatively, try to think or articulate a wish for all beings to achieve liberation from suffering, etc .

Four Thoughts: contemplating each in turn – http://northantsbuddhists.com/the-four-thoughts/

Refuge Prayer: twice in Tibetan, once in English – http://northantsbuddhists.com/the-refuge-prayer/

2.0) A Buddhist Perspective on Grief – Presented by Dee Cormack

“The impermanence of this floating world

I feel over and over

It is hardest to be the one left behind.”

The ultimate relationship we can have is with someone who is dying. Here we are often brought to grief, whether we know it or not. Grief can seem like an unbearable experience. But for those of us who have entered the broken world of loss and sorrow, we realize that in the fractured landscape of grief we can find the pieces of our life that we ourselves have forgotten.

Change is happening all the time—life changing, small, and mostly unnoticeable. Change is part of being human and living in an ever-changing universe. The very fabric that weaves our lives together is impermanent; everything around us arises and ceases every moment and we are inextricably connected to it all.

The last teaching the Buddha gave was his own death—that even the great spiritual sages of the world are subject to impermanence and death. If we resist or reject this universal truth, unhappiness and sorrow will follow because we will be in direct opposition to how things actually exist. Change in and of itself is not a bad thing. The struggle is our relationship to it. Do we use loss, change, and transitions as opportunities for growth or do we resist, struggle and deny?

Grief is often not addressed in contemporary Buddhism. Perhaps it is looked on as a weakness of character or as a failure of practice. But from the point of view of this practitioner, it is a vital part of our very human life, an experience that can open compassion, and an important phase of maturation, giving our lives and practice depth and humility.

Venerable Thubten Chodron, defines grief as adjusting to a change we did not want or expect. Grief comes to the mind because we mistakenly grasp at things as permanent, not as how they actually exist, which is fleeting and transitory. Because of that misconception, we mistakenly believe that we can control the coming and going of things, events and especially people. But due to their impermanence, there is no way that we can control and determine how things will go.

We grieve many things—the loss of a loved one, a career or job, our health, our economic state, our dreams, our worldly possessions, our pets. Such losses are a major part of our lives, yet, when these things end, leave or break, the common response is disbelief. No matter how tenuous a relationship, old or sick a loved one, or fragile a possession, there is still shock when it ends.

Sometimes we cherish our loved ones so much that we can’t imagine going on without them. When they die the grief is so deep because we have projected a future that now will never come. In reality, however, a fabricated future is a mere fantasy. Underpinning the grief many times is a future that is only a dream.

Grieving is a process and these places of sadness, loss, disbelief and denial are normal. Giving ourselves the time and space to experience these strong emotions with compassion, gentleness, and acceptance is the only way to move into, through, and past this time of sorrow.

Ubbiri, one of the first women Buddhists, was drowning in grief as a result of the death of her daughter. Through the help of the Buddha, she discovered truth from within the experience of her own suffering.

Ubbiri came from a high family in Savatthi. She was beautiful as a child, and when she grew up, was given to the court of King Pasenadi of Kosala. One day she became pregnant by the King and gave birth to a daughter whom she named Jiva, which means “alive.”

Shortly after being born, her daughter Jiva died. Ubbiri, terribly wounded by grief, went every day to the cremation ground and mourned her daughter. One day, when she arrived at the cremation ground, she discovered that a great crowd had gathered. The Buddha was travelling through the region, and he had paused to give teachings to local people. Ubbiri stopped for a little while to listen to the Buddha but soon left to go to the riverside and weep with despair.

The Buddha, hearing her pain-filled keening, sought her out and asked why she was weeping. In agony she cried out that her daughter was dead. He then pointed to one place and another where the dead had been laid, and he said to her:

Mother, you cry out “O Jiva” in the woods.

Come to yourself, Ubbiri.

Eighty-four thousand daughters

All with the name “Jiva”

Have burned in the funeral fire.

For which one do you grieve?

I’d like to read something written by Roshi Joan Halifax

“Later, I was to walk the Himalayas with a friend who had recently lost his mother. The fall rains washed down the mountains and down our wet faces. In Kathmandu, lamas offered a Tibetan Xithro ceremony for her. They instructed me not to cry but to let her be undisturbed by grief. By this time, I was ready to hear their words. The experience was humbling for me. And when I finally got to the bottom of it, I found that my mother had become an ancestor. As I let her go, she became a healthy part of me.”

There is no time schedule for grief. It is different for everyone. Many times grief can last in someone’s mind for a long time, and we may even become impatient with ourselves wanting to move on in our lives. Or others may think YOU need to grieve longer as you work out your feelings around loss. Everyone close to the deceased will have their own ways to grieve. It is important to tend to our own process and at the same time be kind and patient with theirs.

When we finally know in our hearts the truth of the fleeting nature of life, then grief becomes a process to help us adjust to the change. It is also an opportunity to look at our own lives, prioritize the important things to hold, and to let go of the rest.

Some of the ways in which we can relate to our grief and work with its strong emotional content is to let go of any blame around our relationship to our loved one—

all the “should haves” —and to learn to accept the situation and ourselves in the here and now.

Thinking in a new way can support our healing. We can rejoice at having had that person in our life. Of all the living beings in the world, we had the good fortune to be close to them and to be part of their world.

We can also pass on their love and goodness to others. Having been the beneficiary of their good hearts, now we can offer that gift to everyone we meet.

We can give their belongings to the needy or a religious organization with a sense of richness and dedicate the merit to their peace and joy and for all their deepest wishes to be realized. Kindly work on any feelings of regret and harmful feelings we may have about them or their death so we don’t die with regrets.

As time goes on memories can show up at any time — anniversaries of the death, birthdays, and holidays. These are precious opportunities to propel us to live our lives with love, compassion, and joy.

Loss is a reality of life. We can do our best to use it as a gift that teaches us to hold our lives lightly and openly. When we remember the impermanence of people and things, we live with greater purpose. And loss can help us have greater compassion towards everyone who, without exception, will experience loss as well.

The river of grief might pulse deep inside us, hidden from our view, but its presence informs our lives at every turn. It can drive us into the numbing habits of escape from suffering or bring us face to face with our own humanity. This is the very heart of Buddhism.

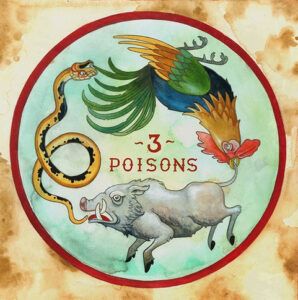

2.0) Developing Bodhicitta to counter anger and Metta Bhavana meditation – Presented by Steve Reynolds

Pop psychology tells us to pound our fists into pillows or to scream at the walls to “work out” our anger. Thich Nhat Hanh disagrees:

“When you express your anger you think that you are getting anger out of your system, but that’s not true,” he said. “When you express your anger, either verbally or with physical violence, you are feeding the seed of anger, and it becomes stronger in you.”

“I have people try to understand why they get angry, what causes it and how it arises.

When you realise these things, instead of manifesting externally, your anger digests itself.”

Lama Yeshe

Metta Bhavana meditation

The development of friendliness, loving kindness. As an antidote to anger.

1. Ourself – generate a sense of being a friend to ourself, being kind to ourself.

2. A good friend – being the best friend we can be to them.

3. An acquaintance, someone we hardly know, or even passed in the street – Feeling friendliness towards them.

4. Someone we are in conflict with, angry with, or is angry with us – Recognising they are people who need friendship and generate that feeling towards them.

5. All beings – Experience a sense of loving kindness to all sentient beings.

—o0o—