Welcome to our twenty sixth online suggested practise for the week. We are now broadcasting a live teaching each Monday evening. If you would like to participate please contact us using the contact form on the homepage.

1.0) If you feel so inclined, begin by reciting the usual prayers (please follow below links for text). Alternatively, try to think or articulate a wish for all beings to achieve liberation from suffering, etc .

Four Thoughts: contemplating each in turn – http://northantsbuddhists.com/the-four-thoughts/

Refuge Prayer: twice in Tibetan, once in English – http://northantsbuddhists.com/the-refuge-prayer/

2.0) How to Contemplate the Four Thoughts – Presented by Bob Pollak

(Precious human birth, impermanence, karma, and suffering)

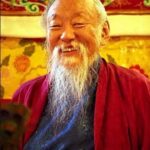

By H.E. Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche (fromGates to Buddhist Practice: Essential Teachings of a Tibetan Master)

Part 1

Each of us is like someone standing on the edge of a crumbling cliff, the earth rapidly breaking away. Telling ourselves, “I’m too hot, too tired, too sick, too busy to do my practice” is like saying we can’t make the effort to run away from the ground eroding beneath our feet. It means we don’t understand the four thoughts. Once we fully comprehend them, we’ll realize the necessity of jumping to safety. What’s more, when we see someone else close to the edge and about to fall, we’ll rush to help; we won’t claim we’re too tired or busy.

To arrive at this understanding, we need to reflect on the four thoughts, to examine them critically, to ask ourselves, “Is it true that I have no alternative but the practice of dharma to break out of the unending cycles of existence?” Through repeated contemplation, sometimes called analytical meditation, we can change our deeply ingrained thought patterns. If we didn’t contemplate, the same old mental poisons—ignorance, attachment, aversion, jealousy, and pride—would come up day after day, year after year. Simply trying to quiet the mind isn’t enough to overcome them. That’s like pushing the “pause” button on a tape recorder so we won’t have to listen to music we don’t like. For as long as we hold the button, we don’t hear anything, but the moment we release it, the music we so dislike starts playing again. In contemplation, we do more than interrupt the tape—we erase it and make a new recording. We transform our ordinary habits of mind, as well as negative thoughts and actions. Then we hear a different sound, one far more harmonious and beneficial.

The ordinary mind is like a legless man, while the winds, or subtle energies, of the body are like a blind wild horse. This combination is what can make meditation so difficult. In our practice, therefore, we address both aspects of the mind – its knowing quality and its quality of movement.

Taming the mind is similar to taming a wild horse. We don’t restrain it tightly with a short tether, which might frighten it and cause it to hurt itself trying to get free. Instead, we let it run in a very large corral. It is not really free, but it doesn’t feel confined, because it has freedom of movement. As we spend more time with the horse, as it gets to know and trust us, it slowly loses some of its fear and allows us to come closer. As it begins to calm down, we can gradually make the corral smaller.

When we want to tame the mind, we shouldn’t try to restrain it at first. Instead of allowing thoughts to run wild, we make a large corral of virtue by transforming negative concepts into positive ones. The mind isn’t really free, yet it isn’t completely confined. This way, we work with mind’s qualities of movement, its unceasing display.

In addition to analytical meditation, we practice in a more non-conceptual way, simply letting the mind relax and fall into its natural state, without any contemplation. Here we cut the mind’s attachment to concepts, its habit of always thinking of past or future, likes and dislikes—as if constantly stirring the water in a muddy pond, never letting it settle and clarify. In so doing, we work with mind’s self-knowing quality.

In this way, we utilize two principles of Buddhist practice. The nonconceptual technique is called shamatha in Sanskrit or zhinay in Tibetan. Zhi means “to pacify obscurations” and nay “to maintain,” so “zhinay” refers to the calm, tranquil abiding in which discursive and distracting thought patterns are pacified and the mind comes to rest one-pointedly.

The contemplative technique, using the rational mind in a skilful, inquiring way, is called vipashyana in Sanskrit or lhagtong in Tibetan, which means “deeper insight,” seeing beyond ordinary seeing. Together, shamatha and vipashyana are like the handle and blade of a sword with which we cut through our holding to the apparent solidity of our subject–object experience. We sever the tight bonds of attachment, ego clinging, and self-interest, thus conquering afflictive emotions and ignorance.

In employing both methods, we work toward resolving duality by cutting attachment not only to ordinary thoughts, but also to non-conceptual, blissful, or extraordinary meditation experiences. We thereby cut the roots of the grosser reflection of the mind’s poisons—samsara—as well as the subtler reflection of the mind’s positive qualities—nirvana. When we alternate these two methods, slowly and subtly our perspective begins to change. What starts as intellectual understanding gradually becomes more personal and experiential. We approach the true nature of mind beyond the extremes of “is” and “isn’t,” thought and no-thought.

—–0——